Rachel Rubin-Sarganis MScPT | Physiotherapist | Parkway Physiotherapy Tuscany Village

What Are Lumbrical Muscles?

Each hand contains four lumbrical muscles, located in the deep palm.

Origin: Every lumbrical begins on the tendon of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle. This is the long muscle that starts in the forearm and travels into each finger to bend the tips of the fingers.

Path: From their starting point on these flexor tendons, the lumbricals run along the inside of the hand toward the fingers, passing in front of the knuckle joints (the metacarpophalangeal joints).

Insertion: They then join the extensor expansion, a sheet of connective tissue on the back of the fingers that attaches to the bones of the middle and end finger segments.

Because they connect a flexor tendon in front to an extensor system on top, the lumbricals literally link the flexor and extensor sides of the finger.

Biomechanics of Lumbrical Muscles

The lumbricals create a combined movement:

They flex the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint, which is where each finger meets the hand, drawing the finger downward at the knuckle.

At the same time, they extend the interphalangeal (IP) joints—the middle and end finger joints—straightening those joints.

This simultaneous bending at the knuckle and straightening of the finger’s mid and tip joints is essential for holding rounded or half-open grips. The lumbricals also help distribute tension evenly between the flexor and extensor systems, fine-tuning finger position and force.

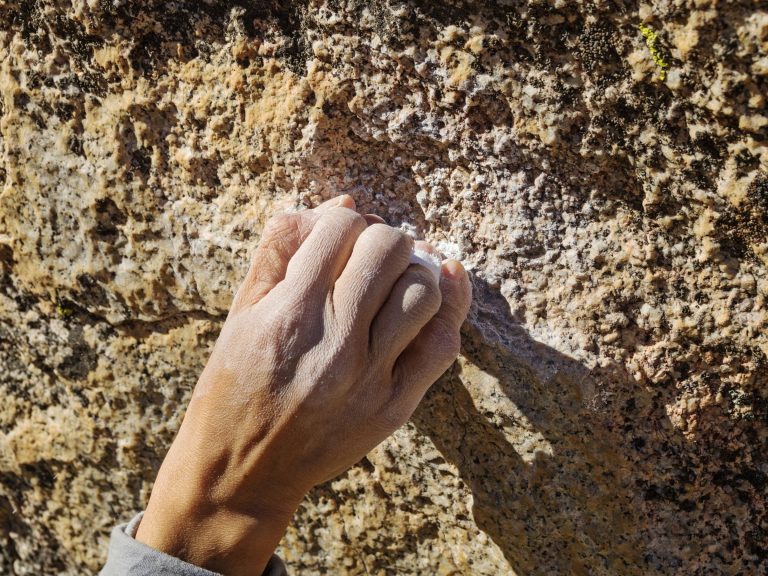

Relevance to Climbing

When a climber uses pocket grips or the three-finger drag position, each finger often bears a slightly different load. One finger may flex more strongly while another is forced into extension. Because the lumbricals span from a flexor tendon to the extensor expansion, they are pulled in opposite directions at the same time.

This dual tension creates shear forces inside the palm.

Sudden moves or slips can sharply stretch the lumbricals, making them prone to strains or tears.

In short, the lumbricals act like dynamic stabilizers that balance forces between the deep flexors and the extensor hood. Their unique cross-system attachments are what allow precise grip control—but they are also what make these muscles vulnerable during the uneven, high loads common in climbing.

How Climbers Get Hurt

Unlike pulley injuries (which fail under pure tensile load), lumbrical injuries are often shear or split-load injuries. Typical scenarios include:

• Pocket pulls or mono-to-two transitions where one finger suddenly bears most of the force

• Dynamic bump or deadpoint moves while holding a drag grip

• Unexpected finger slip causing rapid stretch through the palm

Signs to watch for:

• Sudden “pop” or sharp pain in the palm between the MCPs (often middle-to-ring interval)

• Local swelling, tenderness, or bruising

• Pain when extending one finger while flexing others or when pulling on pockets

Rehab Pathway for Lumbrical Injuries

Step 1 – Decompress & Desensitize

Goal: calm tissue irritation and maintain pain-free motion

• Short-term unloading from pockets and tight drags

• Gentle lumbrical lift drills (table-top MCP flexion with IP extension) to maintain motor patterns

• Light massage or contrast baths for circulation after the first 48 h

• Optional soft buddy taping for comfort and to reduce finger spread

Step 2 – Re-pattern & Strengthen

Goal: restore balanced muscle firing and force sharing

• Lumbrical grip pinch-block holds and finger splay work

• Reverse finger curls to train extensors and balance flexor dominance

• Isometric open-hand hangs to reintroduce low-load tendon tension

• Forearm and shoulder stability exercises to reduce finger overload

Step 3 – Rebuild Dynamic Control

Goal: add load and introduce subtle, sport-specific movement

• Slow grip transitions (open hand ↔ half crimp) under minimal resistance

• Controlled micro-dynos or “bump” drills with deliberate footwork

• Continued lumbrical and extensor training to prevent reinjury

Step 4 – Full Pocket Integration

Goal: safely return to full climbing intensity

• Gradual reintroduction of two- and three-finger pockets and three-finger drags

• Careful session design: low volume, long rests, pain check-ins

• Ongoing emphasis on warm-up, hydration, and recovery habits

4. Prevention Essentials

• Diverse grip training: Rotate pockets, slopers, and open-hand edges to spread load.

• Intrinsic hand workouts: Lumbrical lifts, pinch blocks, and finger splay to keep small muscles resilient.

• Volume management: End hard pocket work early; most strains occur late in sessions.

• Whole-chain support: Strong scapular and core stability reduces surprise load on fingers.

• Daily tendon glides: Maintain mobility of the flexor system and reduce adhesions.

5. Key Home & Gym Exercises

• Tendon Glides – maintain tendon and nerve glide (daily warm-up)

• Lumbrical Grip Pinch Block – strengthen lumbricals (2–3×/week)

• Reverse Finger Curls – balance extensors (2×/week)

• Scapular Stability Drills – shoulder/core support (2–3×/week)

• Slow Finger Rolls – flexor resilience (2×/week)

Final Word

Lumbrical strains require patience and precision. By following the Decompress → Re-pattern → Rebuild → Integrate pathway—rather than a generic “rest then climb” plan, climbers can return to pockets and three-finger drags stronger and more resilient.

Written and reviewed by Rachel Rubin-Sarganis, MPT

Published on September 25, 2025

Last updated on September 25, 2025

Parkway Physiotherapy Tuscany Village

1646 McKenzie Ave #101, Victoria, BC V8N 0A3

Tel. 778-432-3333

Book directly with Rachel: https://parkwayphysiotuscanyvillage.janeapp.com/Rachel